labrys,

études féministes/ estudos feministas

janeiro/junho / 2015 - janeiro/junho 2015

Vertigoes and shades of Brazilianness:

Heterotopias, colonialism and the feminist critique of art

Luana Saturnino Tvardovskas [i]

Abstract

Brazilian’s artists Adriana Varejão and Rosana Paulino produce

in their artworks acute critics against the patriarchal culture, racism

and colonialism, transforming crystallized social narratives and the historical

oppressions on women's bodies and subjectivities. Articulating their productions

with feminist thought and Foucault's reflections on art, this paper proposes

to think them as heterotopic creations, a juxtaposition of temporalities,

spaces and counter-memories.

key-words: women artists, feminism, Brazilian

history, heterotopias, Adriana Varejão and Rosana Paulino

When Michel Foucault, discussing the questions of modern art, in the 1970’s, he called attention to creativity as a practice that would involve acts of transgression and the perversion of means towards unexpected ends. He thus understood modern works of art as an experience of subjective transformation, a critique of stable representations, with a strong anti-platonic presupposition (Tanke, 2009: 128). Containing a materiality and a particular type of thought, some images would work as events generative of effects of rupture. In a dialogue with Deleuze, Foucault glimpsed the images as outside a representative system in which these are taken as simple copies of a real and supposedly true model (2005). He observed that the images discarded by Platonism, such as simulacra, were made up of spaces of difference, and were negotiations that expropriated the already finished images into new compositions: a space of freedom.

Foucault thus rendered problematic a way of thinking post-representational art that would respond to the dynamism, the historical sources and to forces that permeate it. Quoting his words on the French artist Gérard Fromanger (1939):

“The paintings no longer need to represent the street; they are the streets, roads, and paths across continents, to the very heart of China and Africa” (Foucault, 2009a: 353). In this way, art opened itself as a space and an event of passage, of connections and intensities.

It is also possible to analyze contemporary art, from different angles, in its anti-platonic aspect, critical of fixed identities. It shapes up, moreover, as a transgressive and deviant space to be thought from the concept of heterotopia, for, as Foucault asserts, “we do not live in a kind of vacuum, in the interior of which individuals and things can be placed (…) we live inside a set of relationships that define mutually irreducible positionings and which are absolutely impossible to juxtapose” (Foucault, 2009b: 414). For Foucault, the heterotopias – these so-called ‘other spaces’, real but imbued of singular characteristics – would contrast with the social order, the spaces that are stable and available and, as a consequence, we can glimpse that they would affect the subjective experiences. In this sense, the subjectivities and their corporal spatialities would be deeply constituted by the experience of rupture promoted by these positioning and counter-places.

Interesting critical meanings are formulated especially when woman artists produce practices that are de-stabilizing of the subjective, cultural and historical spaces. An acid and vertiginous understanding of Brazilian history is offered us by two contemporary artists, though their visual poetics be unique and most specific. The white artist Adriana Varejão, born in Rio de Janeiro in 1964 and recognized internationally, works the depths and layers of our cultural marks: her best known works re-read the Baroque and Brazilian history in pictures of great materiality where the viscera come out of walls of colonial tiles that can barely bear their weight (images 1, 2). As clearly shown by Paulo Herkenhoff, Varejão shows the saturations of the body of nation, full of historic and symbolic violence (1998). In our retina she rescues, with a sensorial and physical shock, the images of the raw brutality of the civilizatory process.

Image 1 – Adriana Varejão (Rio de Janeiro, 1964)

Image 2 - Adriana Varejão, Azulejaria em carne viva (Tilework with live flesh), 1999.

oil on canvas and polyurethane on aluminum and wood support , 220 x 160 x 50 cm.

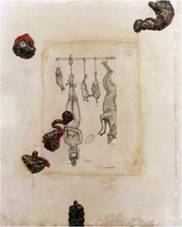

Effectively realistic in her open wounds, the artist is also representational when she creates simulacra of artwork of the past, where she proposes an exercise of heterotopical reflection as she serves Frans Post (1616-1680) – an important painter from Dutch Brazil – on glazed dishes, like a piece of meat, still related to the Brazilian modernist anthropophagy (image 3). The viscera testify that this body is latent still, its blood fresh and hot. Other works refer to the typical decorations of Portuguese kitchens, as in a self-portrait of the artist of 1992, Food, in which the female body is figured as prey and the consumption of food, in a clear exploration of feminist senses (image 4). Her eyes open, her hair dressed as a Chinese, staring at the spectator, Varejão presents herself as ironical and displaced, seeming not to fit into this inverted position by the still alive body.

Image 3 – Adriana Varejão, Carne à moda de Frans Post (Meat a la Frans Post), 1996.

60 x 150 cm

Image 4 – Adriana Varejão, Comida (Food), 1992

oil on canvas , 120 x 100 cm

Rosana Paulino is a black artist born in 1967 in São Paulo, a doctor in visual poetics by the University of São Paulo (image 5). She narrates, through the images of black women, enslaved and raped, a counter-history to the racial democracy as taught by Gilberto Freyre (1950). She points at the forgotten histories of millions of people disconnected from their affections, their memories and territories when forced across the Atlantic.

Image 5 – Rosana Paulino (São Paulo, 1967)

Image 6 – Rosana Paulino, Parede da Memória (Wall of memories), 1994.

8 x 8 x 3cm. Detail Mixed media on cloth

Her works make use of materials and processes such as etchings, sewing and elements of popular culture, referring to the suppression of the African heritages. In the installation Wall of memories (1994) Paulino works with old family portraits creating kinds of amulets called patuás – an element and practice of protection present in the Afro-catholic syncretism in Brazil (image 6). She shows historical images in a critical and incessant repetition, as in her Wet Nurse, in which she exposes monotype prints on cloth, sewn to a panel form (images 7,8). So she discusses the exploitation of the bodies of women used as wet nurses in the Brazilian colonial period, and the violence of these still poignant experiences.

Images 7, 8 – Rosana Paulino, Ama de leite (Wet nurse), 2007.

Soon, I try to discuss how the images of Varejão and Paulino may be thought as heterotopical creations, in a juxtaposition of temporalities, spaces and counter-memories, in exercises of experimentation and of narratives opposite to hegemonic histories. These works have much to say about the places occupied by women in the contemporary cultural imagination, and of their desire and rebellion against these obligations and historical representations in past.

First history: silences

That which was narrated about us, our own history and memory, build in the present the discursive practices and the materiality of our experiences, and is questioned by Tania Navarro Swain (2006). The imagination of other pasts, more than a work of fiction, as this historian points, is part of a constant exercise to formulate other questions about ourselves that are based in new theoretical perspectives. With this question, much discussed in the historiographical debate of the last decades, as emphasized by Paul Veyne (2008), we now observe the past as an unknown territory, on which we impress our concerns, doubts and models of interpretation. We know also that the historical discourse and the history of art itself are fields of legitimating and power capable of incessantly reproducing inequalities, such as those of gender.

Thus, some feminist thinkers have shown us that review the historical sources starting from different theoretical postulates can produce important exercises of freedom. The observation of how women were not simply beings of a secondary category, mere observers of the significant male deeds, but that they have created, resisted and acted in the cultural production of their time, this also is an exercise of empowerment in the present, as Norma Telles indicates (1996:25). For Navarro-Swain there is a need to mistrust the dominant interpretative models, seeking other voices, seeing that

“The ‘master-narratives’ of history (…) conceal the presuppositions that guide them, the values and the representations that model the perceptions, building a homogeneous historical reality, repetitive of the Same(…)” (2006:web).

The works Bastard Son (1992) and Bastard Son II, interior scene (1995) by Varejão, dialogue with these feminist reflections, presenting spatial and corporeal layers in crisis, with different subjective disquiets (images 9, 10). In a parodical re-reading of the canvasses of travelling artists such as Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768-1848), the artist inserts dissonant elements into his masterpieces. Varejão emphasizing the repeated scenes of sexual violence and also formulating marks on the canvass, that allow an access to the past as a body still bleeding.

Image 9 - Adriana Varejão, Filho Bastardo (Bastard son), 1992

110 x 140 x 10 cm

Image 10 - Adriana Varejão, Filho Bastardo II, cena de interior (Bastard son II - interior scene), 1995

oil on wood , 110 x 140 x 10 cm

These works were analyzed by Lilia Moritz Schwarcz that points out how these compositions are a conscious exercise of re-reading, inspired in Debret. It is possible to think about them, from a critical perspective, as a real attack on the canvasses of this painter. Debret having come to Brazil - at the time of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and Algarves - with the French mission of 1816, reproduces in his art the teachings of the French neoclassical school of his cousin Jacques-Louis David, pacifying any subject or sign indicative of tensions in Brazilian society of the XIX Century. Seeking to recreate the ‘picturesque’ landscape of the country, “he learned family scenes, aspects of urban life or made portraits of the local nobility” investing somehow in satisfying the demands of a Portuguese monarchy that had just settled into the country:

“All things are in order and in their places: the nobles shall be dignified, the royalty raised through allegories and parallels with classic antiquity and the slaves…nearly Greeks, with their perfect bodies and muscles on show “ (Schwarcz, 2014: 157).

Image 11 - Jean-Baptiste Debret, Um jantar brasileiro (A Brazilian Dinner), 1827.

15,9 x 21,9 cm. Museu Castro Maya, Rio de Janeiro

Image 12 - Jean-Baptiste Debret, Empregado do governo saindo a passeio (A government employee leaving home), 1820-1830. 19,2 x 24,5 cm. Museu Castro Maya, Rio de Janeiro

This Brazil of harmony, with the relationships between master and slaves most cordial, is the imaginary that Varejão refutes. The characters presented there, a black slave woman, a white master, imperial clerks, an Indian woman – are taken from other paintings of XIX Century, acting in directions that explode the original meanings (image 12). There is the rape of a slave woman by a priest, the punishment of an Indian woman tied and immobilized by men in uniform. The black woman fanning the lady in A Brazilian Dinner by Debret, of 1827, will undergo a double rape in the canvasses of Varejão (image 11). In Bastard Son, the artist shows the hooks that aimed at preventing the escape of slaves to the forests, as portrayed in Punishment imposed on blacks (1816-1831), disclosing that it is about an untamed woman, possibly one that had already tried to escape. The expression of pleasure appears in the face of the male character alone, while the body and face of this woman betray no desire or consent. In Bastard Son II, the white master, that in Debret’s painting was having a meal, rapes her on the dinner table, in front of the children, distracted on the floor, also taken from the canvass.

Image 13 - Jean-Baptiste Debret, Castigo imposto aos negros (Punishment imposed on blacks), 1816-1831. Detail

Varejão also presents a picture over the dinner table, one absent from Debret’s painting, giving an ironical meaning to the Christian religiosity of this seigniorial family. The Indian figure, tied by a rope around the neck, awaits, animalized, a similar fate.

This artistic perspective on Brazilian past reflects still on the dramatic readings of the violations of female bodies, charges that have been made by different areas of the contemporary feminisms. For Navarro-Swain, these narratives are yet to be told, as it is of no interest of the patriarchate to describe their strategies of domination:

"Rape is the great lack in the treaties and manuals, the handbooks of Brazilian History, when praising crossing of breeds, in what refers both to the black slave women and the Indian women. It all happens as if the women were only waiting for the favors and honor given them by their masters, or settlers or frontiersmen when they raped them. It all happens also in a kind of lascivious euphoria, where violence is absent and sexuality is the celebration of a vast feast for crossbreeding. Where the slave however that was not raped several times along her life? This not to speak of the ‘negras de ganho’[ii], made into prostitutes normally and generally? As far as the Indian women are concerned, the image of the prostitute makes again its appearance: Gilberto Freyre comments that they offered themselves to the whites, and the hotter ones rubbed themselves on the legs of those they “supposed to be gods”. (Freyre, 1974:98) (Navarro-Swain,2006:web).

Bastard Son names the circumstance of a conception derived from violence, a son that is fruit of a non-consensual relationship, implying the subjective humiliation and loss of social legitimacy in this Brazil considered as half-caste. In this way the eye of the artist seeks in art the spaces of crisis, that contest the sensual and erotical relations naturalized in the Brazilian historiography. Foucault points out that heterotopias have a function in relation to the space in which they are, being able to “[...]create a space of illusion that denunciates as illusory still any real space, all the positionings in the interior of which human life is compartmentalized” (Foucault, 2009b: 420). Works of art would in such a case denounce, from a fictional imaginary, the historical, political and social positionings in crises in the past and present.

As shown by Margareth Rago, acclaimed intellectuals of the 1920s and 1930s, interpreters of Brazil, and makers of images still current– such as Gilberto Freyre, Paulo Prado, Sergio Buarque de Hollanda and Caio Prado, emphasized the role of sexuality in their readings on our historical roots (Rago, 1998). In this sense they reproduced a multiplicity of prejudices, as those formulated by the juridical and medical discourses on crossbreeding – considered as a consequence of sexual excesses among whites, Indians and blacks, supposed to have generated in our people, in the dawn of colonization, a persistent melancholia, sadness and sloth. There would be, among us, a predominance of instinct over reason; in the words of Paulo Prado:

“The history of Brazil is the disorderly development of these obsessions submitting the spirit and the body of their victims. To that exaggerated eroticism contributed as accomplices - as I have said - three factors: the climate, the land, the indigenous woman or the African slave” (Prado, 1929: 120 apud Rago,1998).

It was so that the discourses on the indigenous and African women were continuously eroticized, making them into “nymphomaniacs” and “wanton”, the sexual dimension has generated references of importance for the interpretation of the characteristics and character of the Brazilian people. It is worth remembering, having resource to Foucault, his reference to theater and the cinema as heterotopical spaces where art permits the invocation of disparate spaces, of fragmented times and the mythical or real contestation of the space we live in. By derivation, the visual arts may also be thought of as a space of opening and of passage to themes, problems and tensions that are, many times, expelled from, or isolated of the center of society.

The violences of gender, the historical and artistic silencings about them, are some of the subjects brought up by Varejão. When copying the travelling artists of the XIX Century as parody, those whose works shaped the Brazilian cultural imaginary, she is attacking the spaces of legitimization of the History of Art (and their mega-fathers, as suggests Mira Schor), but is also inscribing herself as a contemporary who listens to the sounds of rebellion. Her women are explicitly proclaimed as victims of sexual violence, colonial an imperialist violence, but she, herself, violates the picture she paints, showing us an iconoclastic indignation. Thus, it is that this body is found where least expected, behind the canvass, this skin becoming the surface tattooed by art. The ruptures formed vertically in these paintings – with an orifice at the center – allude to the female genital organ, a visceral quality and the embodiment of violation (Chicago and Shapiro, 2010). Vertigoes of a wounded body and of a picture attacked in the manner of “La Fontana”[iii], pointing to the space of incompatibility of Varejão with that that is represented, and her sensorial project of facing us with a body juxtaposed to art, alive, resilient.

Second history: phantoms

Rago, in her article titled “The Exotic Body, a spectacle of difference” points out how the contemporary relations of power are closely connected to the historical violence against women, mainly when they concern the black and Indian populations (Rago, 2010). The histories of black women and men exhibited in scientific expeditions and in human zoos of the XIX Century speak of the perpetuation of an imaginary and misogynous imaginary in which racism justifies the oppression against subjected lives. Rosana Paulino, in her installation Settlement, manipulates a historical photograph of an enslaved black woman, produced by Augusto Stahl (1807-1873) with the objective of ethnographical classification (image 14).

Image 14 - Photography by Augusto Stahl commissioned by Louis Agassiz, Thayer Expedition, 1865.

Between the years of 1865 and 1866, the Swiss Zoologist [naturalized American] Louis Agassiz headed a scientific expedition to Brazil, the so–called Thayer Expedition. It was one of his intentions to collect data with which to prove the superiority of the white ethnic group over the others. (…) Aiming at proving his racist theses, Agassiz commissioned a series of photographs of Africans [and Chinese] of the place, to Augusto Stahl, living in Rio de Janeiro. The ideal was to portray ‘pure racial types’ in photos that would go from the “portrait to photographs of a scientific character where those people, black men and women, would appear in three different positions: from the front, from the back and in profile. This pretended scientism ended up generating, paradoxically, unique photographic registers of the slave population of that city (Press Release, Paulino, 2013).

In the exhibition Settlement, the artist presents the same photograph taken by Stahl, only now printed on cloth, life size, measuring approximately six feet, with sewn interventions and etchings of a fetus in the womb still, roots and a heart (images 15, 16, 17 and 18). If originally this image was intended to determine the racial differences, serving the objectives of better to control and dominate, Paulino produces a radical inversion of the discourses in showing this fragmented body, whose sutures are of impossible integral reconstruction. Besides producing an acid critique of the violence of slavery, the artist, with this installation questions the settlement of African experiences in a Brazilian common ground and the subjective and spiritual reconstruction, even when faced with historical violence.

Images 15, 16, 17 and 18 – Rosana Paulino, Assentamento (Settlement), details, 2013-2015.

Agassiz, the planner of the Thayer Expedition, was the most famous naturalist in the United States, a Harvard Professor to his death. In seeking to oppose the evolutionary theory of Darwin, he clung to the project of proving creationism, catastrophism and polygenesis - the separate origins of human races. An ardent defender of the separation of the races, he criticized crossbreeding and sought to prove the inferiority of the black race. Stephen Jay Gould reproduces a part of a letter in which the scientist tells his mother, in 1850, how for the first time he experienced living together with black people in Philadelphia, as he had never seen a black man in Europe:

I can hardly express the dolorous impression I experienced, particularly because of the sensation by them inspired in me, that goes against all our ideas on the brotherhood of men and unique origin of our species (…) What a disgrace for the white race to have linked so intimately its existence to that of the blacks in certain countries! May God spare us this contact! (Agassiz apud Gould, 1999: 33).

In making use of the anthropometric photographs commissioned by Agassiz, Paulino breaks with this racist imaginary. Taken in the beginning of the history of photography in Brazil, these photos objectified the subjects portrayed, offering no real possibilities of self-representation, as said by Manuela Carneiro da Cunha (1988). Paulino rescues them and fictionalizes based on their fragmentation, their experiences and affections. The keen vision of this woman confronts us with a resilient figure, though in that context the possibilities of exposing oneself as a subject and portraying oneself autonomously were minimal.

In 2014 and 2015 Settlement occupies a space of traumatic memory: the Instituto Pretos Novos (The New Blacks Institute), in Rio de Janeiro (images 19, 20). The Institute, in the Gamboa district of the city, was built as a mode of preserving the historical memory of slavery, for it shelters the old New Blacks Cemetery, rediscovered by chance in 1996, as its exact location had been lost in the city.[iv] This cemetery was operational for about 50 years (1779 – 1830) as the place for the burial of those women, men and children that arrived at Rio de Janeiro through the wharf of Valongo, the larges slave port in XVIII Century America, but did not survive due to bad treatment, diseases, or extreme physical and emotional fragility.

Images 19, 20 – Instituto Pretos Novos (The New Blacks Institute)

Paulino’s choice for this exposition fits into her political and artistic process of revisiting the places of memory, bringing about tensions and re-valuations of the life and past of these individuals forgotten by official history, as in her installation Of Memory and of shades: the wet nurses (Campinas, 2009), shown inside a senzala (an old slave quarters).

The memory of these spaces made into museums – slave quarters and a cemetery – allows us again allude to the text of Foucault, where he specifically mentions cemeteries and museums as heterotopic spaces, filled of temporal and historical experiences of accumulation, but of contradictions and ruptures also. In connection to the cemetery it is interesting to highlight the migration of the old burial place of slaves in the city of Rio de Janeiro, once placed behind the hospital in the Santa Casa De Misericordia (a hospital), to the square of the Church of Saint Rita, and, finally to the wharf of Valongo, with the growth of the slave trade, as studied by Julio Cesar Pereira (2014).

According to Foucault, “Until the end of XVIII Century the cemetery was located in the very center of the city, besides the Church” and it was with the increasing disbelief in the idea of resurrection and in the existence of the soul that a concern began with our mortal remains, “the only trace of our existence in the world and among words” (Foucault, 2009b: 417). Death is individualized, creating a bourgeois appropriation of it, with private spaces for each one in the graveyard. In the case of the New Blacks Cemetery there was no concern in individualizing those bodies, for they were of slaves excluded from the above mentioned order, but even so its jurisdiction was under the responsibility of the Church, that profited from the work.

As was found in recent archeological analyzes, more than 6000 bodies of enslaved persons were cremated, totally or partially, and thrown precariously into common graves, shallow graves (à flor da terra), where there were also found ceramic fragments, Portuguese and English faience and leftover food. According to the historian Reinaldo Tavares :“It was all mixed up (…)If we imagine that the ground of the old necropolis had been used as a deposit of urban rubbish even after it was closed, we see that it was used as a garbage dump even when being used, which, as we see it, is symbolically much graver” (Tavares, 2012:136 apud Pereira, 2014: 133).

The culture of death for the new blacks, mostly belonging to a Bantu tradition, was under serious attack in this context – whether by the absence of funeral rites, by the precarious and violent treatment given the bodies or by the depositing the common garbage with them. José Murilo de Carvalho comments:

Image 21 - Rosana Paulino, Assentamento (Settlement), 2013.

Exhibition view ETEC Polivalente Americana, MAC Americana.

"Death was a very serious matter for the individual and even more for the community. […} The dead person, as long as inhumed according to the rituals, partook in the communion of the forebears, integrated the chain linking the living and dead. In the absence of the funeral rites he became a stray soul, one without a place, forever busy in tormenting his live relatives. (…) It will be necessary now to add to the terror of the slave ships and the slave quarters that of the Cemetery of the New Blacks. (Carvalho apud Pereira, 2014:15).

Decades after its opening and a great movement of bodies with no funeral rites, the growing population starts to grow indignant with the bad smells of the place, fearing diseases that could be transmitted by the air, the so-called miasmas, shown by Foucault, for “[...]there was born an obsession with death as a disease. It is supposed that it is the dead that bring the diseases to the living and it is the presence and proximity of the dead beside the houses, beside the Church, almost in the middle of the street, it is this proximity that propagates death” (Foucault, 2009b: 418).

The choice of this heterotopical space by Paulino, if with great traumatic dimension, puts into question the space of those living, but also the memories silenced in our time (image 21). Her female figure imposes herself ironically by the side of different etchings such as Adam and Eve in the Brazilian paradise and The Daughters of Eve (2014) composed of a study of the fauna - as in the expeditions of Agassiz, but of the shadows of these characters too, that may have had as destination another graveyard lost in this Brazil (images 22, 23). These mortal remains speak to us of ghosts that should continue to haunt us, on whom we may be treading in our blind walk around our towns.

Images 22, 23 – Rosana Paulino, Adão e Eva no paraíso brasileiro (Adam and Eve in the Brazilian paradise) and

As filhas de Eva (The Daughters of Eve), 2014.

As a brief conclusion I would like to emphasize these different temporalities, spaces and historical layers interwoven in the art of Varejão and Paulino, in a project for the construction of other imaginaries on the Brazilian past to oppose the rooted images of our culture. What is thus in the order of the day is the intention of making visible the contemporary feminist practices aimed at self-transformation, the deconstruction of authoritarian political models and of racist and misogynous representations on female bodies. Understanding these practices executed by women through the thought of Foucault on heterotopias widens the vision to the micropolitical resistances, at the level of the subjectivities that also aspire to an ethical, political and cultural transformation.

Biography

Luana Saturnino Tvardovskas is a PhD in Cultural History and

researches about Contemporary women artists in Brazil and Argentina. She

studied at UNICAMP, (Campinas, SP/Brazil); wrote about subject matters

such as body, gender, Contemporary art, feminism, subjectivities, and

power relations. She is a post doctorate researcher at IFCH/UNICAMP/FAPESP

and is author of the book Dramatização dos corpos, São

Paulo: Intermeios, 2015.

Bibliography

ANJOS, Ana Maria de la Merced G.G.G. dos; PEREIRA, Júlio César Medeiros da Silva. 2013. A saga dos pretos novos. Rio de Janeiro: Governo do Rio de Janeiro - Secretaria de Cultura, 5ª ed.

CHICAGO, Judy; SHAPIRO, Miriam. 2010. “Female Imagery” In. JONES, Amelia (ed.) The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. 2ª ed. London/New York: Routledge, pp. 53-56.

CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da. 1988. “Olhar escravo, ser olhado” In. AZEVEDO, Paulo Cesar de; LISSOVSKY, Maurício, Orgs. Escravos brasileiros do século XIX na fotografia de Christiano Jr. São Paulo: Ex-Libris, p.23-30.

DEBRET, Jean Baptiste. 1978. Viagem pitoresca e histórica ao Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Ed. Itatiaia Limitada/São Paulo: Edusp.

ERMAKOFF, George. 2004. O negro na fotografia brasileira do século XIX. Rio de Janeiro: G. Ermakoff Casa Editorial.

FOUCAULT, Michel. 2009a. “A pintura fotogênica”

In. Ditos e escritos III. Estética: literatura e pintura, música

e cinema. Rio de Janeiro: Forense universitária, pp. 346-355.

______________ 2009b. “Outros espaços” In. Ditos e escritos III.

Estética: literatura e pintura, música e cinema. Rio de

Janeiro: Forense universitária, pp. 411-422.

______________ 2005. “Theatrum Philosophicum” In. Ditos e Escritos II: Arqueologia das Ciências e História dos Sistemas de Pensamento. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, p. 230-254.

FREITAS, Marcus Vinicius de. 2002. Charles Frederick Hartt, um naturalista no Império de Pedro II. Belo Horizonte: Ed. UFMG.

FREYRE, Gilberto. 1950. Casa Grande & Senzala: formação da família brasileira sob o regime de economia rural. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Olympio.

______________ 1974. Maîtres et esclaves, la formation de la société brésilienne, Paris, Gallimard.

GOULD, Stephen Jay. 1999. A falsa medida do homem . São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

HERKENHOFF, Paulo. 1996/1998. “Pintura/Sutura”. In: Adriana Varejão. São Paulo: Galeria Camargo Vilaça; reeditado em Imagens de Troca, Lisboa: Instituto de Arte Contemporânea.

KOUTSOUKOS, Sandra Sofia Machado. 2010. Negros no estúdio do fotógrafico. Campinas, SP: Editora da Unicamp.

LAGO, Bia Corrêa do. 2001. Augusto Stahl: obra completa em Pernambuco e Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Capivara.

NAVARRO-SWAIN, Tania. 2003. “As heterotopias feministas, espaços outros de criação”. Disponível em

http://www.tanianavarroswain.com.br/brasil/anah2.htm Acesso em 10 out. 2013.

___________ 2006. “Os limites discursivos da história: imposição de sentidos”. Revista eletrônica Labrys estudos feministas. Janeiro/ junho. Disponível em http://www.labrys.net.br/labrys9/libre/anahita.htm Acesso em 17 nov. 2013.

NERI, Louise (org.). 2001. Adriana Varejão. [textos Louise Neri

e Paulo Herkenhoff] São Paulo: O Autor.

PEREIRA, Júlio César Medeiros da Silva. 2014. À flor da terra: o cemitério dos pretos novos no Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond.

PRADO, Paulo. 1929. Retrato do Brasil. Ensaio sobre a tristeza brasileira. 3" ed. São Paulo, s/ed.

RAGO, Margareth. 2008. “O corpo exótico, espetáculo da diferença”. Revista eletrônica Labrys, Estudos Feministas, n.13, jan./jun. Disponível em: <http://www.tanianavarroswain.com.br/labrys/labrys13/perspectivas/marga.ht> . Acesso em 05 jul. 2010.

___________ 1998. “Sexualidade e identidade na historiografia brasileira”.

In. LOYOLA, Maria Andreia. A sexualidade nas Ciências Humanas. Rio

de Janeiro: Eduerj, pp. 175-200.

SCHOR, Mira. 2010. “Patrilineage” In. JONES, Amelia (ed.) The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. 2ª ed. London/New York: Routledge, pp. 282-289.

SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz; VAREJÃO, Adriana. 2014. Pérola imperfeita: A história e as histórias na obra de Adriana Varejão. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó.

STRAUMANN, Patrick (org.). 2001. Rio de Janeiro, cidade mestiça: nascimento da imagem de uma nação. [ilustrações e comentários de Jean-Baptiste Debret; textos de Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, Serge Gruzinski e Tierno Monénembo] São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

TANKE, Joseph J. 2009. Foucault's philosophy of art: a genealogy of modernity. London/New York: Continuum.

TAVARES, Reinaldo Bernardes. 2012. Cemitério dos Pretos Novos, Rio de Janeiro, Século XIX: uma tentativa de delimitação especial. Mestrado em Arqueologia, Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.

TELLES, Norma. 1996. Cartografia brasílis ou: esta história está mal contada. 3ª.ed. São Paulo: Editora Loyola.

VAREJÃO, Adriana. 2009. Adriana Varejão: entre carnes e mares=between flesh and oceans. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó.

VEYNE, Paul. 2008. Como se escreve a história; Foucault revoluciona a história. [4ª Ed.] Brasília: Editora UNB.

WILLIS, Deborah. 2002. Reflections in Black: a history of Black photographers, 1840-1999. London/New Yok: W.W. Norton & Company.

WILLIS, Deborah; WILLIAMS, Carla. 2002. The Black female body: a photographic history. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

translation:Ricado Lopes

[i] This article was presented at the IX Colloquium Michel Foucault, Recife-Brazil in April 2014.

[ii] “Negros de ganho” were slaves who could circulate in the cities making small paid jobs.

[iii] The artist refers to the painting by Lucio Fontana (1899-1968).

[iv] During a remodeling in the house of the Guimarães, located at Pedro Ernesto Street, 36, the workers found human bones when digging. The city was notified and they came to the conclusion that it was The Cemetery of the New Blacks.

labrys,

études féministes/ estudos feministas

janeiro/junho / 2015 - janeiro/junho 2015